Anti-Racist Activism on College Campuses

Just as past generations of young activists were inspired by the actions of black students in 1960, black student activists are again leading the youth movement.

Madeline Nicholson

Ekstern Skribent

Madeline Nicholson

Ekstern Skribent

There has been a long standing history of anti-racist student activism in American lead by black students, and decades later the leaders of the movement are still those with the most on the line.

In 1960 four students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University sat down at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., and refused to leave. Those young men — Ezell Blair Jr., 18; Franklin McCain, 19; Joseph McNeil, 17; and David Richmond, 18, made their stand on February 1st, 1960 and within three days were joined by more than 300 others. Within months, the sit-ins had spread to more than 50 cities, and lunch counters across America began rapidly desegregating.

The actions of the so-called Greensboro Four led directly to the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, after instance from young activist Ella Baker wanting to harness the impact of the sit-ins and coordinate the effort. SNCC went on to play a major role in the American Civil Rights movement, instrumental in the Freedom Rides and in voter registration efforts across the South. And the momentum sparked by the Greensboro four directly contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in public spaces.

Arguably what is most powerful about the actions of the Greensboro four was by demonstrating that even a small group of students can have a long standing impact. They inspired students across America to take action and mobilize.

The model set by the Greensboro four and SNCC later inspired student protests on college campuses throughout the 1960s and 1970s calling for the end of the draft and our withdraw from Vietnam, the creation of Chicano studies programs, women’s liberation, gay rights, nuclear non-proliferation, and later Apartheid divestment.

Just as past generations of young activists were inspired by the actions of black students in 1960, black student activists are again leading the youth movement.

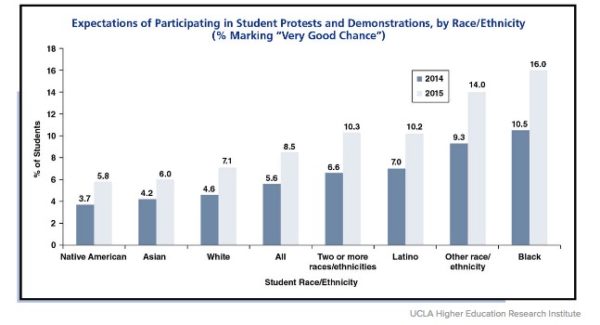

A survey conducted in 2016 by the Higher Education Research Institute found that interest in political and civic engagement has reached the highest levels since the study began 50 years ago. Nearly 1 in 10 incoming first-year students expects to participate in student protests while in college.

The rising interest in activism coincides with some recent successful protests by college students on issues of racial equality. In 2014 Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters staged “die-ins” on dozens of college campuses to raise awareness of police brutality, although the universities administrations were quick to dismiss and discipline the protesters. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement cracked open a racial dialogue in America, which included college campuses, and while BLM protestors were shut down by the universities. Students from within institutions began organizing to address issues of racial inequity in their own learning community, and with great success.

In November of 2015 University of Missouri President Timothy Wolfe and university Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin, the two most powerful men at the university, resigned after pressure from the student body due to their failures to address racial inequality and a series of racist incidents. In August the university suddenly informed graduate students it would no longer subsidize their health insurance. Tensions escalated through the fall. In September, Payton Head, president of the Missouri Students Association, said that passengers in a pickup truck had shouted racial epithets at him. In October a swastika drawn in feces was found on a dormitory bathroom wall. Later that month students united under the name Concerned Student 1950– a group named for the year the university admitted its first black student– protested the racist incidents at homecoming parade. They surrounded Mr. Wolfe’s car and when the protestors refused to move, they were dispersed by the police. Throughout the incident, Mr. Wolfe stayed in the car, which then allegedly bumped at least one of the protesters as it drove away. Mr. Butler, a graduate student and one of the protesters at the parade, began a hunger strike on November 2, refusing to eat until Mr. Wolfe resigned. In November the University of Missouri football team said they would join Mr. Butler’s protest, boycotting all football-related events until Mr. Wolfe was out of office. The next day, their coach, Gary Pinkel, tweeted a photo of the team together and said he stood behind the players. The boycott by the football team instantly transformed the University of Missouri’s crisis into a national crisis and brought the paucity of minority students, faculty members, and top administrators at colleges and universities across the country to the national attention. The boycott by the team forced conversations throughout the nation about incidents of racism on college campuses. The football teams boycott came just days before their Saturday game against Brigham Young University. Forfeiting the game reportedly would have cost Missouri $1 million USD. Their status as student athletes allowed the players turned activists to apply a level of financial leverage to the protest movement unavailable to their fellow students, it was this very financial pressure that resulted in the resignation of President Wolfe and Chancellor Loftin.

The events at Missouri not only proved watershed for student athletes, who demonstrated their power within institutions of higher education, but student activists engaged in anti-racist work across the nation. The Missouri resignation contributed to the successful forced resignation of Mary Spellman Dean of Claremont McKenna College in California after mishandling racial incidents that same year.

The events at Missouri are also evidence that national conversations about race will increasingly pull in higher education, said Chad L. Williams, an associate professor of African and African-American studies at Brandeis University.

“College campuses see themselves as existing within a bubble, worlds unto themselves,” said Mr. Williams, who has incorporated recent racially charged events into his teaching.“But you cannot divorce the issues that take place on college and university campuses from the broader context.”

The events at the University of Missouri sparked the formation of the Black Liberation Collective, a coalition of Black students groups who are dedicated to transforming institutions of higher education through unity, coalition building, direct action and political education. The newly formed group organized the #StudentBlackOut, a national day of action towards ending racial injustice in response to the incidents at the University of Missouri. Demonstrations include walk-outs, protests, and rallies with all students dressed in all black attire, a symbol of the black power and the BLM movement. Demonstrators gathered at preeminent institutions such as Harvard, Tufts and Princeton, and state schools such as Towson University alike. Many students demanded schools give free tuition for black and indigenous students and that institutions divest from for-profit prisons. Some schools called for change specific to their respective institutions. At University of Cincinnati, students called for police who were at the scene of a shooting of an unarmed black man to be barred from patrolling campus. At Princeton, protesters occupied the university president’s office, asking the administration to end the use of the “masters” title for heads of colleges, which without mentioning race, were “historically vexed”. At the University of Toronto in Canada students held a rally in solidarity with the University of Missouri. Students at Tufts University walked out of class, using the hashtag #thethreepercent to highlight the school’s percentage of black students. In an effort to address the lack of representation of Black students and faculty. Wesleyan University students have some demands of their own as well. “We, as students of color at Wesleyan University, have been neglected by the administration at this school,” organizers wrote on their site. “We are demanding that our administration make justice and equity a priority. With the support of fellow students, faculty, and staff, we are standing up.” Their demands include the hiring of an equity advocate for the university, establishment of a multicultural center, and tracking of faculty and staff bias and microaggressions.

The momentum from the #StudentBlackOut continued. During the summer of 2015 the Black Student Union secured a commitment from administrators at UC Berkeley for the Fannie Lou Hamer Resource Center. Not long after that, officials at Georgetown University apologized for their link to slavery and promised admissions advantages to slaves descendants whom the school may have benefited from sale. In 2016 California State – Los Angeles announced the Halisi Black Scholars Living Learning Community in response to the Black Student Union’s demands for “safe housing” for African American students. At Boston College in 2017 following a pair of racist incidents and a subsequent walkout by students protesting what they call the administration’s years-long failure to directly confront racism on campus. And most recently, during the spring of 2018 the Black Student Union at Colorado College successful demanded the eradication of the ‘West In Time’ requirement, which mandated each student take two courses of western history or philosophy which the student body felt further privileged a Eurocentric pedagogy, following a series of racist anti-black incidents on campus.

Student activism seems to be experiencing a revival, and last fall’s incoming freshman class appears more likely than any before it to take advantage of opportunities to participate in this part of the political process,” said Kevin Eagan, director of CIRP. “We observed substantial gains in students’ interest in political and community engagement across nearly every item on the survey related to these issues.

American youth are more mobilized, active, passionate, and organized than any generation in recent decades. But increasingly the consequences for protest and political action are becoming stratified along racial lines.

For young black and minority activists amidst the college admission process the history and focus of their activism can determine their entrance to University. While colleges and Universities across America have no official policy regarding recruitment and acceptance of anti-racist activists a recent poll suggests a more covert process is taking root.

A recent poll conducted by a New Republic researcher and journalist revealed that white admissions counselors were, on average, 26 percent less likely to respond to the admission emails of black students whose interests and involvements focused on anti-racism and racial justice. The gender of the counselor and the student also mattered.

White male counselors were 37 percent less likely to respond to anti-racist black students. And when black women students committed to anti-racism were emailing white male counselors, they were 50 percent less likely to receive a response. Although, white male admissions counselors were twice as likely to respond to black women if they were committed to fighting environmental degradation instead of white racism. This indicates that it was not activism that depressed the response rate of anti-racist black students, but rather the racial focus of their activism.

These findings have grave ramifications for anti-racists activists and minority students everywhere applying for higher education. Student activists of color are paying a higher price for their activism, and are at a greater risk than their white allies in the struggle.

The events at the University of Missouri demonstrate that once black students make it to struggle for racial equality continues. Between 2015 and 2016, the number of reported racial incidents at colleges and universities jumped nearly 25 percent, according to data from the US Department of Education. Making colleges increasingly dangerous and hostile spaces for students of color. Only 28 percent of African-American, Latinx, and Asian-American students report feeling safe or included on campus, compared to 45 percent of white students, according to survey data by the Jed Foundation and the Steve Fund. The fund was founded in honor of Stephen Rose, a black Harvard graduate who committed suicide in 2014.

While the current generation is more politcally engaged than many in recent decades those who often engage in activism are students of color with the most at stake.

Students of color, primarily black students are the most likely to be politically active, but also pay the highest cost when it comes to college admittance, places where black students are already disadvantaged. This research from New Republic reflects the need for white ally support in youth movements.

Let this be a call for action. White student allies need to move from behind their computers, to put aside the articles they share on facebook in solidarity, and support black and POC leadership, but they also need to leverage their white privlege and take a more active role in the anti-racist struggle. It is time to see more white students marching into the halls of power to demand racial equality on college campuses and in society.

Vi trenger din støtte! Du kan hjelpe oss i arbeidet mot diskriminering, fordommer og hat ved å dele denne artikkelen eller ved å gi en gave.